Assignment: Interior and exterior photography of a newly built homeless shelter

Construction Photography | Editorial Photography

Client: Absher Construction, Tacoma Rescue Mission

Location: Tacoma, Washington

Year: 2020

First, an aside. It was the summer of 2000. I was working on a student research project in Tanzania and had a small point-and-shoot film camera with me. After dropping it a few times, the film door latch broke. I had to rely on layers of green duct tape to keep the door shut. To change a roll of film, I would peel the tape and re-tape the door afterwards. Every shot was carefully considered.

Once back in New York, I was excited to develop the film and see my photos. The giraffes in the photos from my trip to the Serengeti were barely visible. They were not the towering, magnificent animals I would see on the pages of the National Geographic and was hoping for in my own pictures. To figure out why, I picked up books on photography, then started taking photography classes. The internet was America Online on Windows 95, so learning was more hands-on.

After learning a little about photography, I started toying with the idea of being a photographer. By then, I was a fishery biologist in Juneau, Alaska. Capital City Weekly was a free community newspaper in Juneau that you’d read while grabbing lunch. The one you’d find on street corner stands and by front doors of shops. They paid a little for photos of community events around town, so I signed up as a freelancer and felt exhilarated to be paid for photography.

Through their referral I landed my first commercial shoot. A national pharmacy association hired me for a series of photos of a local pharmacy. The pharmacy was to be featured in the association’s calendar. The job paid $600, which I promptly spent on a Canon flash I needed for the job. Without knowing how to photograph with a flash, I scrambled to make it work.

I was emboldened by the success of that shoot. I thought all I needed was to quit my fishery job and I would be on the way of becoming a full-time photographer. Although I was good at quitting jobs, it took me seven years and a move to another state to learn how to start building a successful, full-time photography business.

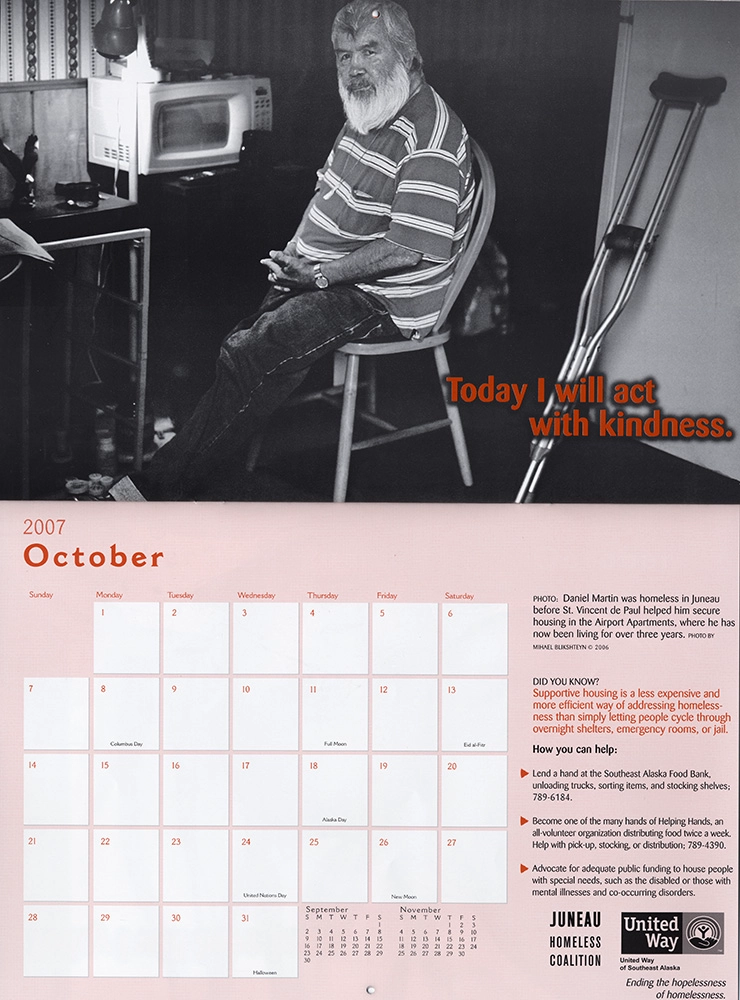

Editorial photography is how I started on my path of a photographer. It’s like a secret handshake. Photography opens otherwise closed doors. It lets you into other people’s lives, often in an intimate, unguarded and unexpected ways. When I was still in Juneau, I worked with the United Way of Southeast Alaska to help them bring attention to homelessness. Along with a couple of other photographers, we created a series of images of people able to find permanent housing, as well as those not so lucky. That series was one of the last projects I shot on film.

I worked with the local homeless shelter, The Glory Hall, to create a short video to advocate for the first Housing First facility in Juneau. Housing First is an approach to ending homelessness by providing permanent housing with few or no preconditions, thus enabling many to improve their quality of life.

This video was my first attempt at film-making. At that time I had no training or experience in making videos, and borrowed the gear from a local filmmaker to make it happen. However, the video ended up being featured on KTOO, the local public media station.

Once I moved to Washington, I was happy to offer my photography skills to Real Change, Seattle’s award-winning newspaper. The paper provides those with low or no income immediate economic opportunities. I ended doing a couple of photography projects with them.

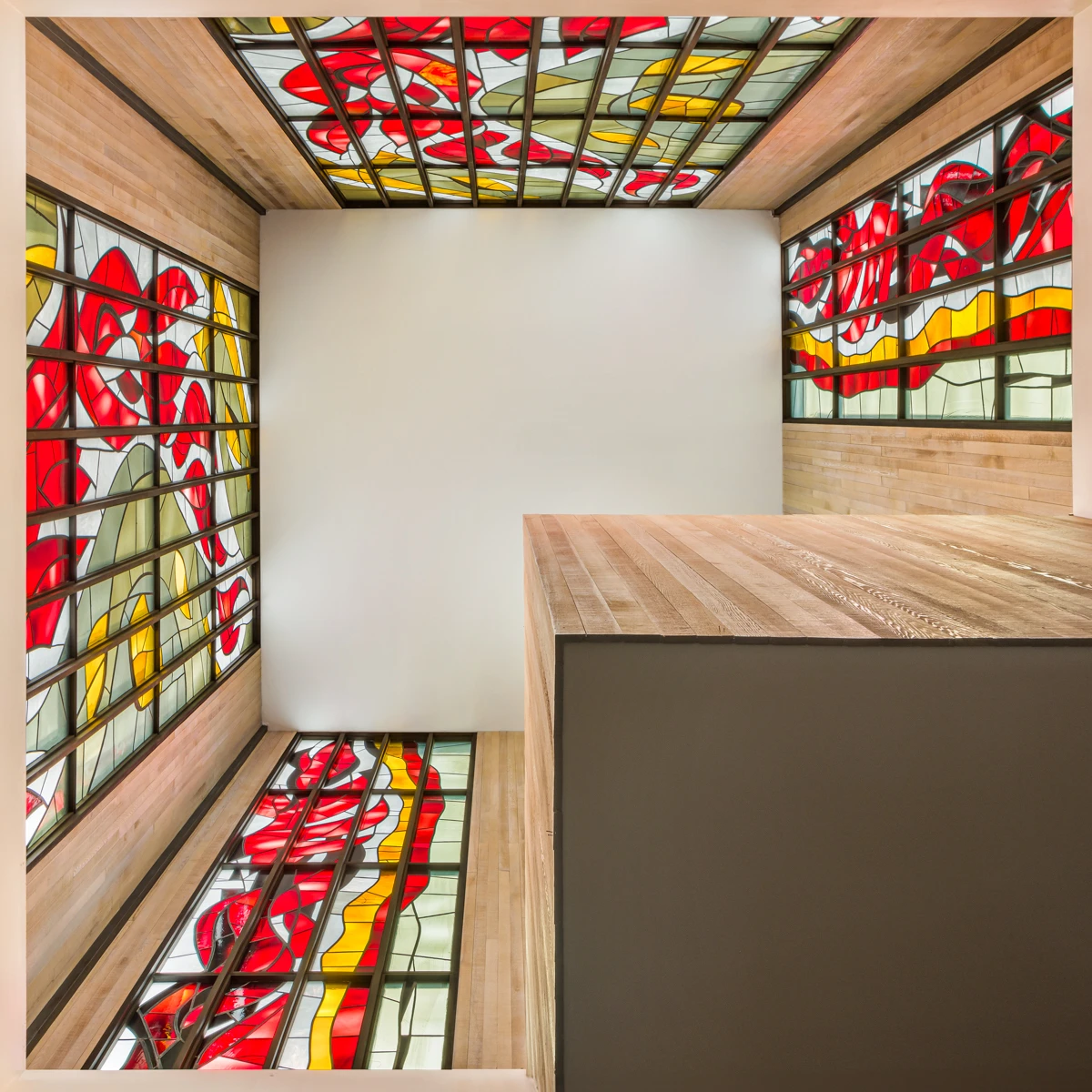

Photographing the newly constructed Women’s Shelter in Tacoma was thus a special project for me. Construction was managed by Absher Construction and the photos will be used by the Tacoma Mission Center as well. What was once a storage facility on the campus of the Tacoma Mission Center was turned into modern temporary housing. The shelter houses women experiencing homelessness. With 36 beds in two rooms, a laundry room, storage lockers and showers, it’s a welcome respite for those in emergency situations. The second floor of this new facility provides the badly needed office space for some of the staff of the Tacoma Mission Center